Caravaggio’s St. John the Baptist – a work of art, sacrilege, or child pornography?

It all started in 1602 when an influential Roman aristocrat, banker, and an art collector, and enthusiast Vincenzo Giustiniani showed his friends a magnificent painting bought from Caravaggio. This was Amor Vincit Omnia, a composition also known as The Amor Victorious (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin), representing a nude, winged boy holding arrows in his hand and smiling seductively at the onlooker. Influenced by this work, another collector and also an aristocrat and banker, with whom Giustiniani spent a lot of his free time, Ciriaco Mattei, commissioned a canvas for the name-day of his oldest son (Giovanni, meaning John) with John the Baptist as the main protagonist.

At that time the author of the painting had already enjoyed great renown in the Roman artistic community, after completing paintings for the Contarelli Chapel (the Church of San Luigi dei Francesi), as well as finishing the canvas for the Cerasi Chapel (Santa Maria del Popolo). The riotous life of Caravaggio, the conflicts in which he willingly entered, the insults and impertinences which he gladly issued towards his colleagues, carrying weapons and even wounding an adversary with a dagger, all of which he had committed, were treated rather lightly since the temperamental painter could always count upon his influential clients, which included cardinals (e.g. Francesco Maria del Monte) and other Roman aristocrats.

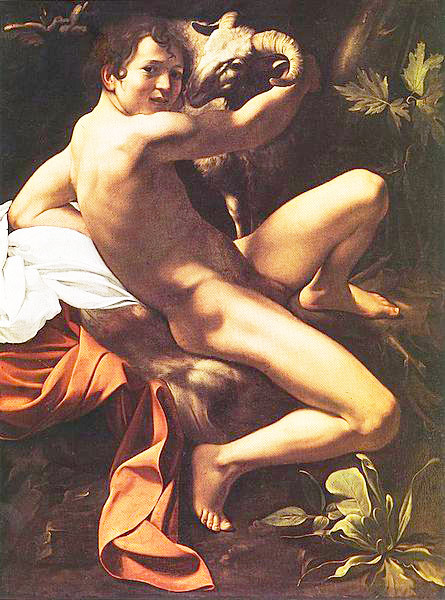

At that time Caravaggio lived in the palace of the Matteis who cared for him, commissioning subsequent works. When the name-day gift was finished, art connoisseurs were astounded – they saw a figure which was well-known to them: the placement of the body, the raised leg, a strong curve of the body were certainly reminiscent of one of the twenty nude youths (the so-called ignudi) painted by Michelangelo on the vault of the Sistine Chapel, almost a century prior. However, they were also able to recognize someone whom they had been more familiar with –a boy named Cecco, with the features of a child from the suburbs and a lively and joyous personality, who was a servant, perhaps a painting aide, and certainly a frequent model for Caravaggio. He was the one that posed for him for his recently completed work The Amor Victorious, the canvas which was so proudly exhibited among the greatest works of his collection by the marquis Giustiniani.

Without a doubt John the Baptist presented on Caravaggio’s painting made for Ciriaco Mattei, is far removed from the image with which we usually associate this saint, therefore we could ask, is it really him? There are documents which clearly confirm this: in 1614 after the death of Ciriaco an inventory of his collection was made, in which this painting is attributed as such and under such a title as a result of a will was given by Giovanni Mattei to add to the collection of another great admirer of Caravaggio's work and a man who possessed several of his earlier works – Cardinal Francesco Maria del Monte. However, it was rather difficult to accept such a non-standard representation of the New Testament prophet, which is evidenced by the fact that in 1627 (a mere year after the death of cardinal del Monte), it was claimed that the painting depicts Corydon – a shepherded who was doomed by his ill-fated love for a slave by the name of Alexis – a character from one of Virgil’s pastorals. In 1628 the canvas found itself in the papal collections, to finally end its life in the warehouses of the Capitoline Museum, where it was stuck for another three centuries. It was discovered by accident in the study of the mayor of Rome in 1950, and it returned in the glory befitting the work (of also discovered anew) Caravaggio. But even then questions were posed about the identity of the represented figure. At times it was seen as a free interpretation of one of Michelangelo’s ignudo, then again an image of an unspecified shepherd, and finally, Paris who was raised among shepherds. It was also connected with the figure of Isaac. Identifying the boy with the son of Abraham, who was ultimately spared by his father, sacrificing a ram, seemed to satisfy everyone. However, this was not Isaac! Caravaggio's first biographer, Giovanni Baglione – a painter himself and a fervent opponent of the artist in question – confirms that the painting depicts Jesus's cousin, the one who prophesized the coming of the Messiah and who in traditional iconography is presented with characteristic attributes – a camel-skin robe covering his body, a thin wicker cross, a lamb and a vessel with water referencing the baptisms given by John.

As we know the image of St. John had been widely disseminated in art. But generally, he was shown at the moment of baptizing Jesus, or in a very popular during the Renaissance scene of adoring the Child, where he appeared as a peer of Christ – either alone or accompanied by his mother St. Elizabeth. Less frequently, he was presented as an eremite in the desert. However, the late Renaissance brought iconographic novelties. One of these was introduced by Leonardo da Vinci, in 1515 painting John as a nude youth. The ambiguity of this painting, showing the saint even without a loincloth (which was later added), the lack of all his characteristic attributes had to appall since in time the title of the painting was changed turning its protagonist into… Bacchus. An equally provocative St. John was created in Florence in 1561. He was painted by Bronzino, an almost nude saint, who was, in reality, a portrait of the son (John) of the painter's patron – Cosimo I de' Medici (Bronzino’s St. John the Baptist). Therefore, Caravaggio was not an innovator here, although it must be admitted that the age of the boy upon the painting (more or less twelve years) may shock. This is still a child, not a youth, painted by both Leonardo and Bronzino. Historians claim that this may have been Caravaggio’s way of pointing out a rather mysterious phrase from the Gospel, where we can read “And the child grew and became strong in spirit; and he lived in the wilderness until he appeared publicly to Israel” (Luke 1, 80). This fragment could provide some sort of a justification for the young age of the John depicted by the painter, but does it justify the lack of any of the prophet’s attributes in the painting? And what does this “becoming strong in spirit" mean? Furthermore, how should the figure of the horned ram be interpreted? Can it be associated with the Lamb of God – the symbol of the sacrifice of Christ? Definitely no. It is just the opposite: the horns of the animal indicate a mature (also sexually) male, which leads to some rather different associations. And what about the lush plant life which surrounds the saint? Without a doubt, this is not a barren desert but rather the pristine Arcadia – the mythical land of happiness. Was it then a conscious attempt of mocking borderline sacrilege by Caravaggio, who was known for his unorthodox attitude to religious subjects? Doubtlessly the artist mocked our traditional habits: in reality, we can see upon the canvas – as if on stage – the youthful actor Cecco, who once plays the role of Amor, and later the role of St. John the Baptist. He changes costumes, but he really does not want us to believe that he is anybody else but a beautiful boy. This ambiguity, as well as eroticism of the painting, which was not an object of private devotion, but above all a work of art, places the onlooker in front of an almost conceptual work. It is the viewer who must decide where is the thin line between John – a youthful shepherd and the frivolous Cecco.

Caravaggio has been known to frequently use the faces and bodies of commoners to paint the figures of saints. And thus in painting Mary Magdalene he portrayed his tired and half-asleep lover. Let us look at the childish illiterate – St. Matthew with the features of a Roman vagabond (the initial version of the painting), who is assisted by an angel in putting together the words of the gospel (Contarelli Chapel), or the Virgin Mary at the threshold of a house, who is reminiscent of a single mother looking for an opportunity to earn a few coins from a man walking through the dark alley (Madonna dei Palafrenieri), not to even mention the appalling corpse in the painting The Death of Our Lady, in which the Virgin Mary is presented as a drowned woman taken out of the Tiber, with green skin, and a bloated stomach. Caravaggio takes the saints off the altars and clouds, where they levitated among cherubs and places them in the dark alleys of Rome. He shakes the art enthusiasts of those times and destroys their esthetic habits, but also the long-lasting canons of perceiving sainthood. He is brutally arrogant, but also shows the hypocrisy of idealized art to the fullest. He is interested in the here and now, the real life, which he preserves as a photographer would. You do not want me to show you the people that you see from the windows of your carriages – the wandering sex-boys, prostitutes, and beggars, but I – he seems to be saying – will paint them and you will hang them in your salons and chapels. The only thing I will do is bestow the names of saints upon them because that you are willing to accept in the name of art.

The mastery with which Caravaggio constructs the composition of St. John the Baptist, the way in which he "spills" light on the nude body of his protagonist, captures the moment in which the surprised boy beckons us with his gaze, are fascinating indeed. Let us take a look at how he plays with ambivalence. Right in front of our eyes, we see neither a child nor a man, the figure neither sits nor lies, is surprised by our presence but not completely, as if he was awaiting our voyeuristic gaze. Everything in the painting is not what it seems, it is a play of meanings and erotic overtones. If the light is an emanation of divinity, while shadow is the symbol of evil, then let us look at how they place themselves upon John's body. As a result, we ourselves do not really know, if our eyes are looking at an innocent in his nudity saint hermit, or an undressed boy, whose representation balances on the border (at least by today's standards) of child pornography.

And let us stop at this border for a while. Such a question is posed by historians, who are not willing to admit or are unconscious of the fact how taste, as well as morality, have changed over the span of many years separating us from the moment of the creation of certain works of art. The question is even more (or perhaps most of all) irritating, because we are dealing with an exceptional work, created by a painter with an unorthodox approach to numerous subjects, and as we know, art, and especially exceptional art, should not be censored. A few years ago an argument arose over this very censorship in Germany in connection with the aforementioned Amor Vincit Omnia. On one side there were those who condemned the masterpiece found in the Gallery of Old Masters in Berlin to isolation in the warehouse, on the other – the supporters of freedom in art. Such antagonism is in reality a start of a discussion on the question of whether a work of art can be considered child pornography. Everybody can see and speaks about the homoerotic theme in Caravaggio's work, but let us take a moment and consider what could have stimulated the artist's interest in beautiful boyish faces and bodies, which definitely aroused erotic desires, longing, and lust.

Caravaggio was not only a difficult, impetuous, boastful, and over-ambitious man. He was also familiar with the meanders of the human psyche. Being in the palaces of his patrons allowed him to achieve financial stability, which he had lacked for a long time, to become familiar with the world of the wealthy, to look upon life which he could have never accessed before. But even then during the period of this “prosperity”, he went out at night in the company of armed colleagues, at the regret of his biographer Baglione, to immerse himself in the dark, narrow alleys and spend time with prostitutes, weirdos who were equally rebellious as he and lived in hiding, poets wanted by the law, as well as seekers of fortune and fame from many different walks of life. He also had to see petty thieves, underage, hungry beggars, and those who were slightly more handsome awaiting the appropriate gesture of a nightly passerby. All of this provided him with the knowledge of the human psyche, but most of all its darkest secrets. And it is from the depth of this secret life, developing alongside the official, private one, that paintings such as The Amor Victorious or St. John the Baptist emerge, similarly to those painted previously for cardinal del Monte. The recognition and bringing to light of these hidden trends in life were for the ingenious painter, an artistic challenge, but the artifacts themselves were most likely an expression of gratitude for the support, given to him by his faithful clients. The images of beautiful boys were destined for them – the refined erudites, knowledgeable in literature and philosophy, who desired works of art that would be outside the boundaries of the broadly available art. Today we would have said that they were searching for works, which could stimulate their discussions, analyses, and comparisons, but they were also to be objects of intellectual and emotional seduction, erotic nourishment. In such circles subjects of ideal love were willingly discussed, ancient Greece and the pederasty born within its borders – a social and educational phenomenon - were subjects of frequent talks. The love which bound a mature man with a boy was considered by (mainly) Athenians as a highly erotic emotion that allowed one to achieve an ennobled ideal of life. It was not always (or not only) understood in a sexual dimension. The beauty of a young boy was after all a reflection of the divine idea of Beauty and Good. Such love did not in any way exclude sexual relations with women, but it was not they who aroused the minds of the then men. A true bonding of souls took place on the dimension of intimate contact between a mature man and a boy, however never against the will of the latter. His love was to be acquired through presents, attention, patience, but most of all erudition. Men fell in love with boys, but they also suffered due to their constantly changing moods or not returning their sentiments. According to Plato, there were two kinds of love (Eros): the one directed towards women and based on “earthly” desires, and the “divine’ one allowing for a true symbiosis of soul and body, which blossomed between a mature man and a boy. Let us add that the objects of such desire were generally youths between the ages of twelve to eighteen. After that period, the practice of pederasty was (for the passive partner, meaning the boy), something inappropriate and ridiculed. Then this love transformed into a deep and life-long friendship. The ideas developed by Plato found their continuation in the Neoplatonic Renaissance philosophy, whose supporters were convinced that sexual contact between a man (twenty years old or older) with a boy led to the providing the latter (through sperm) with virtues, abilities, and knowledge. This belief was so widespread that for example in sixteenth-century Florence – as studies have shown – even fifty percent of the male population could have had sexual relations with adolescents[1]. The subject of pederasty was also undertaken by contemporary works such as the dialogue L’Alcibiade, fanciullo a scola (Alcibiades the Schoolboy) from 1630, whose author Antonio Rocco, shows the process in which the student Alcibiades under the influence and the oratory supremacy falls under the spell of his teacher Filotimo. In this text there is also no shortage of references to Nature, whose – as the author would have us believe – greatest creation is young boys. Can love towards them be in opposition to it? – he concludes with the words of Filotimo.

After the Council of Trent, which made sexual contacts with minors punishable (also by death for homosexual practices) they did not disappear, especially among people who, due to their noble birth and high social status, could be above the law. They did, however, become more discreet. And here we are once again faced with the question regarding Caravaggio's work. Is his immortalization of boys in more or less erotic poses, only a result of wanting to please the then art enthusiasts, who very willingly bought such representations, or was it a need of the painter himself, an expression of his preferences? There is no single answer. Although being familiar with the highly "unorthodox" life of the artist, the second option cannot be excluded. Such an assumption may further be confirmed by the text written by an English traveler and aristocrat Richard Symonds, who in 1650 (meaning 40 years after Caravaggio's death), during his stay in Rome wrote in his journal that Cecco was for Caravaggio "his own boy ... that laid with him”. Was Cecco simply a servant, or was he also a boy with whom the artist maintained erotic relations, this shall remain a mystery and a hypothesis, just as the assumption that (as some claim) sharing a table and a bed with a servant was nothing extraordinary and did not have to have sexual connotations. However, it is certain that Cecco (Francesco Boneri) came into the artist’s life around 1600 and lived with him until 1605 at vicolo San Biagio. And he was also the most frequent model for his paintings, not only the ones with erotic overtones[2].

In Rome, we can encounter this controversial image of St. John the Baptist painted by Caravaggio twice. One of the paintings is found in the Capitoline Museums, the other painted in the very same year (1602) which is its copy – adorns the Palazzo Doria Pamphilj. Within its walls, we can also find another version of this composition, this time by an unknown author. These versions are a testimony of the interest this painting aroused.

Caravaggio often returned to the figure of John the Baptist. It is the most frequent motif of his work. The aspect that combines subsequent representations is the youthful appearance of the saint and his distinctly exposed nudity, although in no other painting is it so bold as is our painting. The other paintings also include single attributes of the saint, but – most importantly – his visage is bereft of the frivolous smile. It is replaced by an expression of melancholy, almost sadness. There are two such images in Rome – one in the Palazzo Corsini (Galleria Nazionale d'Arte Antica), the other – in Galleria Borghese. The latter was painted prior to the artist's sudden death (1610) – while fleeing, wandering and tired, prematurely aged, bereft of a home and a future. It is difficult to not be under the impression that this painting is an almost ideal illustration of such a state of mind. It is sad, withered and so very far removed from the image of John from the Capitoline Museums, where he is full of life, eroticism, and youthful vigor.

Caravaggio, Saint John the Baptist, 1602, oil on canvas, 129 x 94 cm, Musei Capitolini

[1] Michael Rocke, Forbidden Friendships, Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence, 1998

[2] Cecco is identified with Cecco del Caravaggio, a painter active in Rome in the years 1610-25, whose paintings to a large extent referenced those of Caravaggio.

If you liked this article, you can help us continue to work by supporting the roma-nonpertutti portal concrete — by sharing newsletters and donating even small amounts. They will help us in our further work.

You can make one-time deposits to your account:

Barbara Kokoska

BIGBPLPW 62 1160 2202 0000 0002 3744 2108

or support on a regular basis with Patonite.pl (lower left corner)

Know that we appreciate it very much and thank You !